Earthquake Magnitude, Energy Release, and Shaking Intensity

Earthquake magnitude, energy release, and shaking intensity are all related measurements of an earthquake that are often confused with one another. Their dependencies and relationships can be complicated, and even one of these concepts alone can be confusing.

Here we'll look at each of these, as well as their interconnectedness and dependencies.

Magnitude

The time, location, and magnitude of an earthquake can be determined from the data recorded by seismometer. Seismometers record the vibrations from earthquakes that travel through the Earth. Each seismometer records the shaking of the ground directly beneath it. Sensitive instruments, which greatly magnify these ground motions, can detect strong earthquakes from sources anywhere in the world. Modern systems precisely amplify and record ground motion (typically at periods of between 0.1 and 100 seconds) as a function of time.

Magnitude is the size of the earthquake. An earthquake has a single magnitude. The shaking that it causes has many values that vary from place to place based on distance, type of surface material, and other factors. See the Intensity section below for more details on shaking intensity measurements.

Types of Magnitudes

Magnitude is expressed in whole numbers and decimal fractions. For example, a magnitude 5.3 is a moderate earthquake, and a 6.3 is a strong earthquake. Because of the logarithmic basis of the scale, each whole number increase in magnitude represents a tenfold increase in measured amplitude as measured on a seismogram.

When initially developed, all magnitude scales based on measurements of the recorded waveform amplitudes were thought to be equivalent. But for very large earthquakes, some magnitudes overestimate true earthquake size, and some underestimate the size. Thus, we now use measurements that describe the physical effects of an earthquake rather than measurements based only on the amplitude of a waveform recording. More on that later.

The Richter Scale (ML) is what most people have heard about, but in practice it is not commonly used anymore, except for small earthquakes recorded locally, for which ML and short-period surface wave magnitude (Mblg) are the only magnitudes that can be measured. For all other earthquakes, the moment magnitude (Mw) scale is a more accurate measure of the earthquake size.

Although similar seismographs had existed since the 1890's, it was only in 1935 that Charles F. Richter, a seismologist at the California Institute of Technology, introduced the concept of earthquake magnitude. His original definition held only for California earthquakes occurring within 600 km of a particular type of seismograph (the Woods-Anderson torsion instrument). His basic idea was quite simple: by knowing the distance from a seismograph to an earthquake and observing the maximum signal amplitude recorded on the seismograph, an empirical quantitative ranking of the earthquake's inherent size or strength could be made. Most California earthquakes occur within the top 16 km of the crust; to a first approximation, corrections for variations in earthquake focal depth were, therefore, unnecessary.

The Richter magnitude of an earthquake is determined from the logarithm of the amplitude of waves recorded by seismographs. Adjustments are included for the variation in the distance between the various seismographs and the epicenter of the earthquakes.

Moment Magnitude (MW) is based on physical properties of the earthquake derived from an analysis of all the waveforms recorded from the shaking. First the seismic moment is computed, and then it is converted to a magnitude designed to be roughly equal to the Richter Scale in the magnitude range where they overlap.

Moment (MO) = rigidity x area x slip

where rigidity is the strength of the rock along the fault, area is the area of the fault that slipped, and slip is the distance the fault moved. Thus, stronger rock material, or a larger area, or more movement in an earthquake will all contribute to produce a larger magnitude.

Then,

Moment Magnitude (MW) = 2/3 log10(MO) - 9.1

See the Magnitude Types Table (below)for a summary of types, magnitude ranges, distance ranges, equations, and a brief description of each.

For More Information on Magnitudes

- Magnitude Types Table

- How much bigger is a magnitude 8.7 earthquake than a magnitude 5.8 earthquake? Try it yourself calculator

- Magnitude Educational Resources

Energy Release

Another way to measure the size of an earthquake is to compute how much energy it released. The amount of energy radiated by an earthquake is a measure of the potential for damage to man-made structures. An earthquake releases energy at many frequencies, and in order to compute an accurate value, you have to include all frequencies of shaking for the entire event.

While each whole number increase in magnitude represents a tenfold increase in the measured amplitude, it represents an 32 times more energy release.

The energy can be converted into yet another magnitude type called the Energy Magnitude (Me). However, since the Energy Magnitude and Moment Magnitude measure two different properties of the earthquake, their values are not the same.

The energy release can also be roughly estimated by converting the moment magnitude, Mw, to energy using the equation log E = 5.24 + 1.44Mw, where Mw is the moment magnitude.

Intensity

Whereas the magnitude of an earthquake is one value that describes the size, there are many intensity values for each earthquake that are distributed across the geographic area around the earthquake epicenter. The intensity is the measure of shaking at each location, and this varies from place to place, depending mostly on the distance from the fault rupture area. However, there are many more aspects of the earthquake and the ground it shakes that affect the intensity at each location, such as what direction the earthquake ruptured, and what type of surface geology is directly beneath you. Intensities are expressed in Roman numerals, for example, VI, X, etc.

Traditionally the intensity is a subjective measure derived from human observations and reports of felt shaking and damage. The data used to be gathered from postal questionnaires, but with the advent of the internet, it's now collected using a web-based form. However, instrumental data at each station location can be used to calculate an estimated intensity.

The intensity scale that we use in the United States is called the Modified Mercalli Intensity Scale, but other countries use other scales.

For More Information on Intensity

- The Modified Mercalli Intensity Scale

- Magnitude vs Intensity - Grades 4-12 activity: magnitude, intensity

- Intensity distribution and isoseismal maps for the Northridge, California, earthquake of January 17,1994, USGS Open-File Report 95-92.

- Intensity Educational Resources

Examples

These examples illustrate how locations (and depth), magnitudes, intensity, and faults (and rupture) characteristics are dependent and related.

Intensity of Shaking Depends on the Local Geology

Intensity of Shaking Depends on Depth of the Earthquake

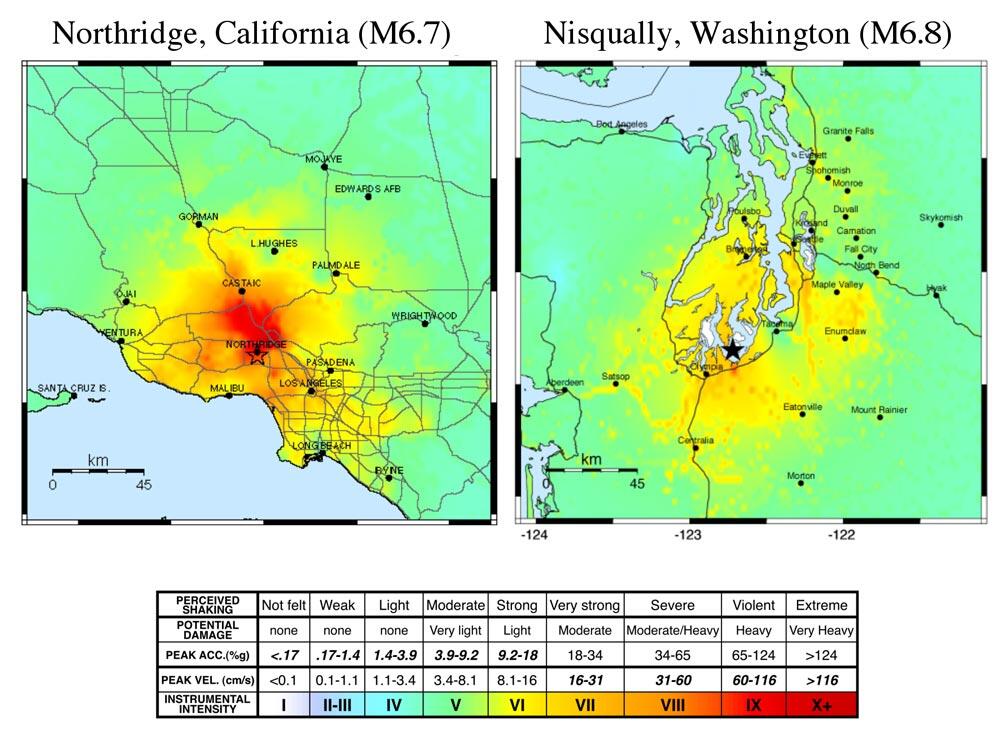

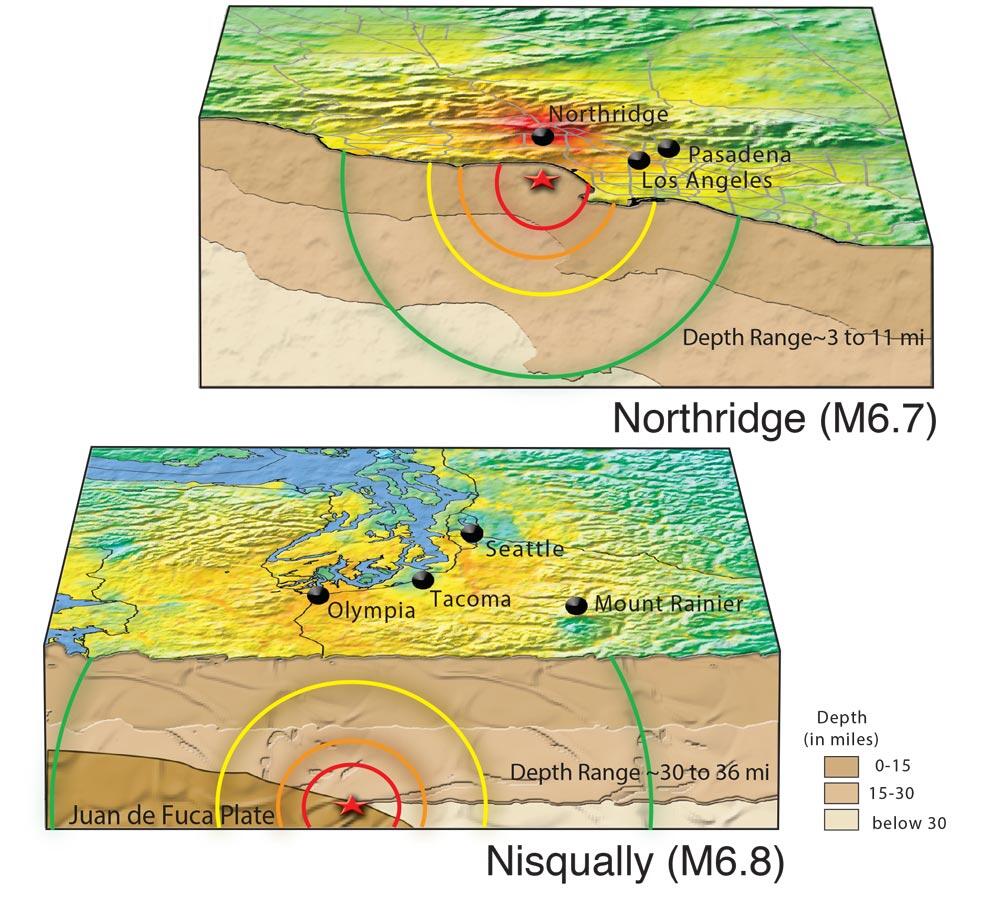

The shaking from the M6.7 Northridge, CA earthquake was more intense and covered a wider area than the slightly larger M6.8 Nisqually, WA earthquake.

The reason is shown by the two cartoon cross-sections below. There was more shaking in the Northridge earthquake because the earthquake occurred closer to the surface (3-11 miles), as opposed to the Nisqually earthquake's deeper hypocenter (30-36 miles).

Moment Release (Energy) of Many Small Earthquakes vs. One Large Earthquake

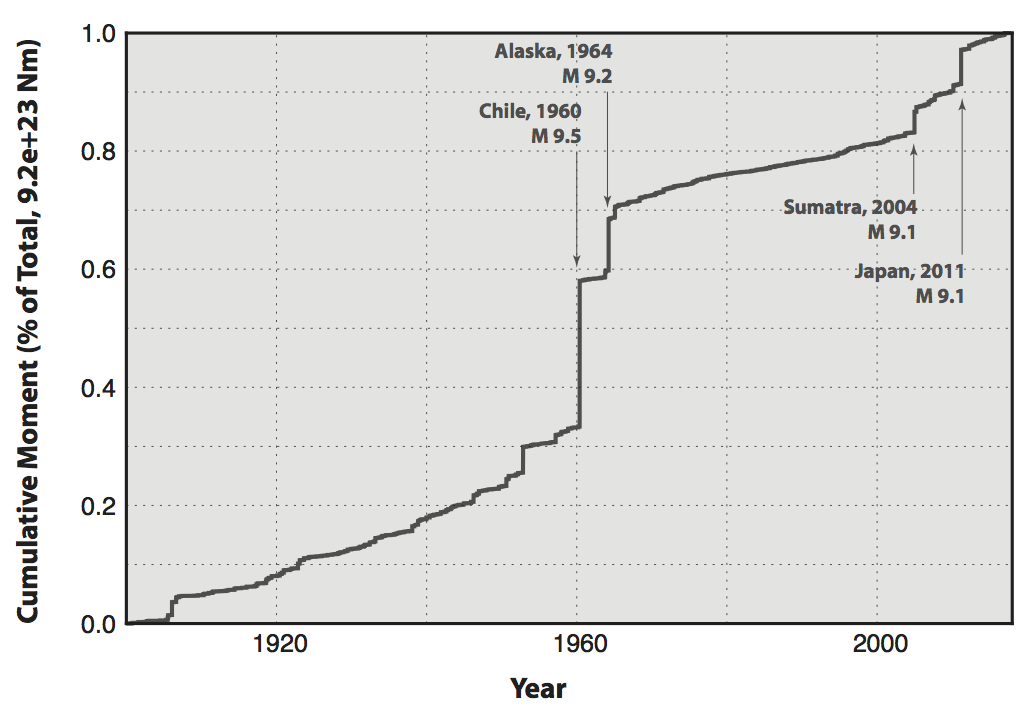

The small- and moderate-size earthquakes that occur frequently around the world release far less energy that a single great earthquake.

What Would it Take to Make a Magnitude N Earthquake?

If we sum all of the energy release from all of the earthquakes over the past ~110 years, the equivalent magnitude ~ Mw9.95.

If the San Andreas Fault were to rupture end-to-end (~1400km), with ~10m of average slip, it would produce an earthquake of Mw 8.47.

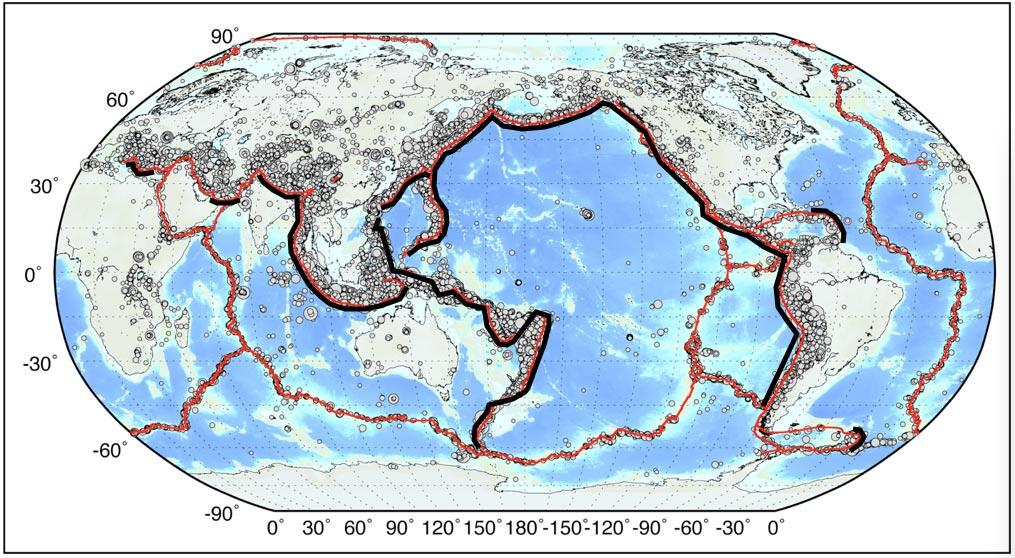

If the South American subduction zone were to rupture end-to-end (~6400km), with ~40m of average slip, it would produce an earthquake of Mw 9.86.

You would need ~14,000km fault length, with a seismogenic thickness averaging 40km (width of 100km), to slip and average of 30m to produce an Mw 10.

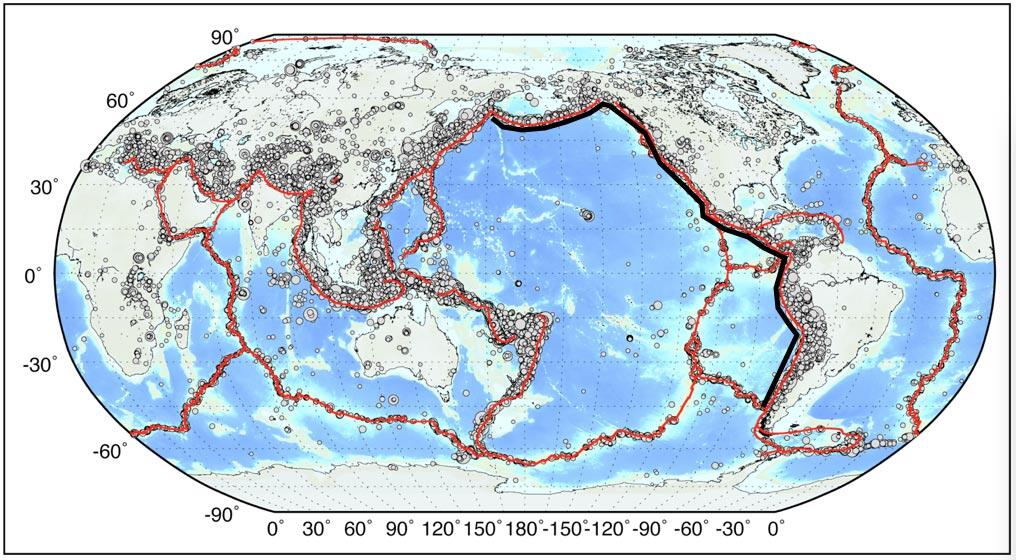

You would need ~80,000km of fault length with an average seismogenic width of 100km to produce an Mw10.5. All of the subduction zones in the World, plus some adjoining structures amount to ~40,000km, and the circumference of the Earth is ~40,000km, so an Mw 10.5 is highly unlikely.

Thanks to Gavin Hayes and David Wald for providing much of the material for this page.