- last updated September 27, 2017 1:40 PST

On September 2, 2017, there was a M5.3 earthquake east of Soda Springs, Idaho. It caused moderate shaking over a broad area of southeastern Idaho, northern Utah, and western Wyoming.

The earthquake has been followed by a sustained and highly active sequence of smaller earthquakes (aftershocks), more than we would typically observe for earthquakes of this size. Because of this, we are providing earthquake forecast scenarios, below, that we'll update regularly as long as the sequence continues.

About the M5.3 Mainshock

The M5.3 earthquake occurred as the result of normal faulting within the shallow crust on a fault dipping at an intermediate angle either to the west or to the east. This faulting style is typical of earthquakes located in the Intermountain Seismic Belt, a prominent NS-trending zone of seismicity in the Intermountain West, and a region of moderate-to-high seismic hazard. This region is characterized by movement along north-trending, east- and west-dipping range-bounding normal faults that accommodate gradual horizontal extension of the Earth’s crust.

Earthquakes occur frequently in the Intermountain Seismic Belt, and it is unlikely that this sequence is related to the Yellowstone volcanic region which lies over 200 km to the northeast.

Past Earthquakes in This Area

South and Central Idaho have experienced at least 14 other M5+ earthquakes within 300 km of the September 2, 2017 earthquake over the preceding century. The largest was the October 28, 1983, M6.9 Borah Peak earthquake, which struck about 250 km to the northwest of the September 2, 2017 earthquake. The Borah Peak earthquake is the largest known to have occurred in Idaho, and resulted in two fatalities, two injuries, and considerable damage in Challis, Idaho.

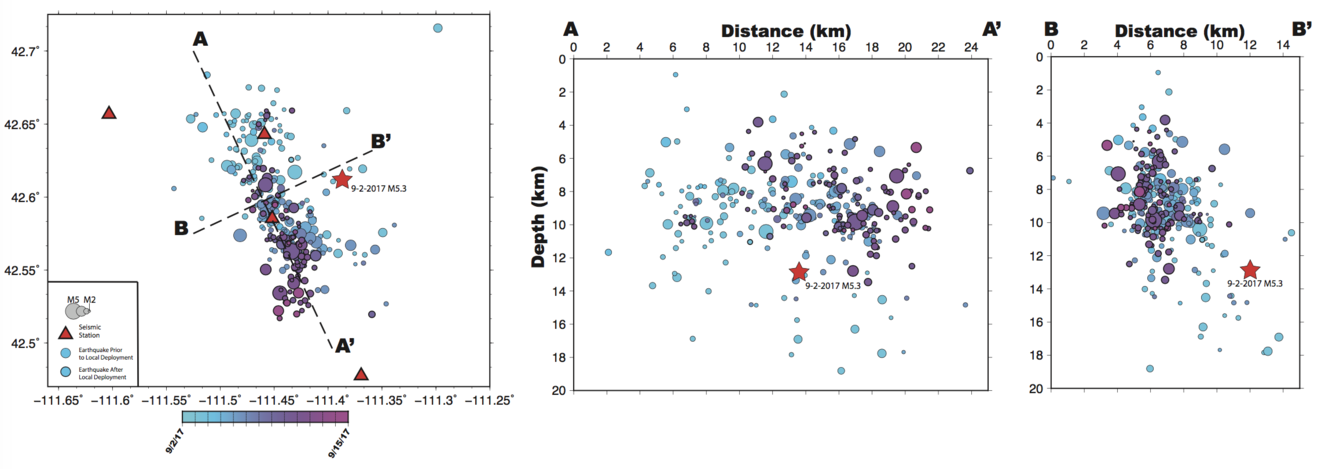

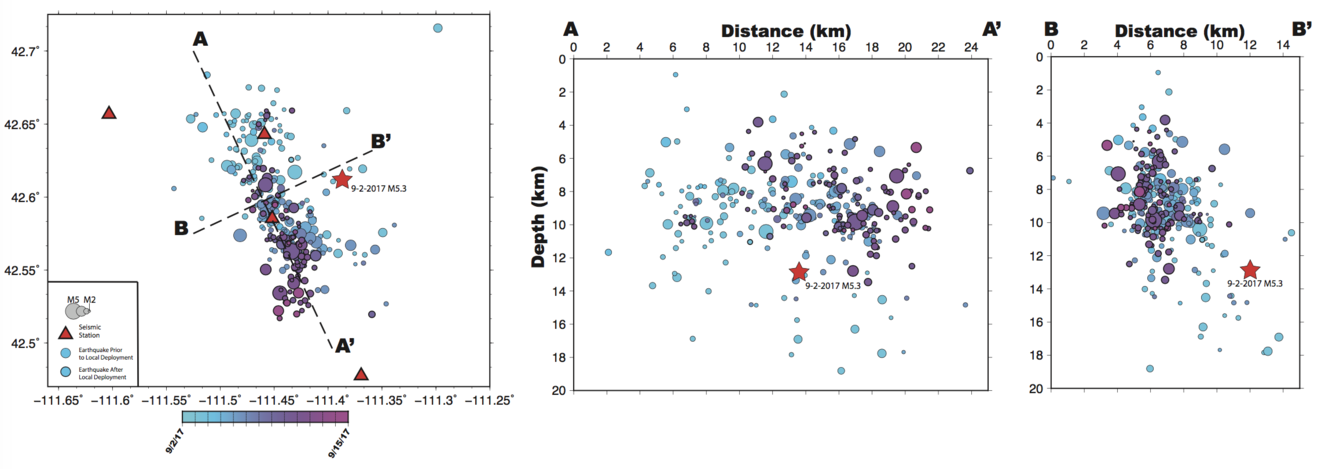

Improved Monitoring

The University of Utah Seismograph Stations and the USGS are collaborating to improve earthquake monitoring in the region of the recent seismicity. Eight seismic stations have been installed within 60 miles of the mainshock. Data from these seismic stations are being used to more accurately locate the earthquakes and detect smaller events. These data are helping researchers map the causative faults and will improve our understanding of earthquake hazard in the region.

Earthquake Forecast

The M5.3 Soda Springs Sequence is particularly active, producing more aftershocks on average than other earthquakes of this magnitude. In terms of future larger earthquakes in this area:

- When there are more earthquakes, the chance of a large earthquake is greater, which means that the chance of damage is greater.

- Idaho and Montana experience earthquakes. While earthquakes are not that common, it is also not surprising to see earthquakes in these areas.

- This sequence may have damaging earthquakes in the future, so remember to: Drop, Cover, and Hold on if you feel the ground shaking.

Due to the active and ongoing nature of this sequence, we have developed an earthquake forecast for continuing seismicity. No one can predict the exact time or place of any earthquake, including aftershocks. What our earthquake forecasts do is give us an understanding of the chances of having more earthquakes within a given time period. We calculate this earthquake forecast using a statistical analysis based on past earthquakes in similar tectonic environments, as well as the aftershocks recorded to date for this sequence.

Our forecast changes as time passes due to the decay in the frequency of aftershocks, larger aftershocks that reinvigorate the sequence, and changes in forecast modeling based on the earthquake data collected. Similar to weather models, our models will also change with more data and information. The longer this sequence goes on, the more we learn about what it will do in the future.

We have taken a detailed forecast and developed three scenarios that we consider to be the most likely. These scenarios are for the following month, but earthquakes will continue to be possible at later times. The forecast was last updated on Sept. 28, 2017. We will continue to update the forecast as more information becomes available.

Here are the three scenarios or possibilities for the month starting Sept. 28, 2017, based on earthquake forecast models:

- Scenario #1 (most likely: 90-95% chance):

The sequence will continue to decay over the next month, which means there will be fewer earthquakes. Earthquakes above M3 may be felt by those in the area, and occasional spikes in activity may be accompanied by additional M4 or larger earthquakes, but with none larger than the M5.3 mainshock. While all earthquake sequences decay over time, there are several other possible outcomes, which are listed next. - Scenario #2 (less likely than Scenario #1 but possible with 5-10% chance):

A similar sized or larger earthquake than the M5.3 mainshock may occur. This situation is often referred to as a “doublet” when a similar sized earthquake follows the original earthquake that kicked off the sequence. Doublets have occurred in places around the world, but they are not very common. - Scenario #3 (the least likely scenario but still possible with less than 1% chance):

A much larger earthquake than M5.3 could occur, up to and including the M7 range, in which case we would call what has happened prior to any larger earthquake a foreshock sequence. We have seen this happen in other places around the world, with the most notable being L’Aquila, Italy in 2009. It is important to understand that this is a highly unlikely scenario, but we cannot ignore the possibility of this occurring.

This forecast is for one month, but the sequence may continue past that timeframe. The probabilities will be updated periodically.

What You Can Do About the Earthquakes

If you feel an earthquake, remember to: Drop, Cover, and Hold On. An earthquake may feel small at the beginning but can build in shaking intensity very quickly, so it is best to take the precaution in small earthquakes, as well as larger ones. Preparing for earthquakes is also important - see our Earthquake Preparedness resources. Earthquakes don’t give us any warning that they are coming, so it is important to be prepared for them just in case.

What Scientists are Doing to Learn More About These Earthquakes

Due to its remote location, there is a lot to be learned yet about this sequence. We are working with scientists and students at Utah State University, University of Idaho, and other institutions to get a better understanding of the geologic processes causing these earthquakes. We are assisting with a program of research to determine areas that are most affected, any changes in local hot springs, and other issues.

What Fault is Causing All This Shaking?

We aren’t certain which fault these earthquakes are occurring on, but we have some strong suspects. The specific fault responsible for this earthquake and the subsequent aftershocks is currently under study by the USGS and scientists at Utah State University. Science investigation teams are getting out in the field to deploy temporary seismic instruments and find out more information about the causes and consequences of this earthquake swarm.

The geology of this area is intriguing and complex. The M5.3 earthquake and subsequent aftershocks occurred beneath the Aspen Range of southeastern Idaho, approximately 15 km (9.3 mi) SE of Soda Springs, Idaho, and 33 km (20 mi) north of Montpelier, Idaho. The basic geology of the region consists of folded and thrust-faulted rocks of Permian to Cretaceous age. These thrust faults shifted these rocks from west to east approximately 100 million years ago and created the mountains from southeastern Idaho to western Wyoming, a region termed the Idaho-Wyoming-Utah fold and thrust belt. Subsequent to this compression, the area has been subjected to east-west extension that has created active normal faults.

To the southwest, these faults are clearly seen (the Wasatch Fault, East/West Cache Faults and the East/West Bear Lake Faults). The West and East Bear Lake faults probably continue north of the lake. These two faults are responsible for the formation of these valleys, including the valley through which the Bear River flows from Montpelier to Soda Springs. These normal faults probably started moving several million years ago, and indicators of offset can be seen from Georgetown to east of Bear Lake. The current earthquake sequence could have occurred on one of these faults.

However, there are number of suspects in determining which fault is the main culprit. And indeed, there could be multiple faults at play - in fact, focal mechanisms suggest that several different faults are involved, because there are both normal and strike slip mechanisms. We hope to resolve this issue the coming weeks and months with additional scientific studies.

Teamwork Built this Forecast and the Science Investigation

We’d like to acknowledge our many hard-working partners in Utah State University, University of Utah, Idaho Geological Survey, Yellowstone Volcano Observatory, and other institutions. We’d also like to acknowledge our colleagues in New Zealand, who worked hard in developing forecasts and scenarios in their country. Their hard work has inspired the development of these forecast scenarios.

For More Information

- last updated September 27, 2017 1:40 PST

On September 2, 2017, there was a M5.3 earthquake east of Soda Springs, Idaho. It caused moderate shaking over a broad area of southeastern Idaho, northern Utah, and western Wyoming.

The earthquake has been followed by a sustained and highly active sequence of smaller earthquakes (aftershocks), more than we would typically observe for earthquakes of this size. Because of this, we are providing earthquake forecast scenarios, below, that we'll update regularly as long as the sequence continues.

About the M5.3 Mainshock

The M5.3 earthquake occurred as the result of normal faulting within the shallow crust on a fault dipping at an intermediate angle either to the west or to the east. This faulting style is typical of earthquakes located in the Intermountain Seismic Belt, a prominent NS-trending zone of seismicity in the Intermountain West, and a region of moderate-to-high seismic hazard. This region is characterized by movement along north-trending, east- and west-dipping range-bounding normal faults that accommodate gradual horizontal extension of the Earth’s crust.

Earthquakes occur frequently in the Intermountain Seismic Belt, and it is unlikely that this sequence is related to the Yellowstone volcanic region which lies over 200 km to the northeast.

Past Earthquakes in This Area

South and Central Idaho have experienced at least 14 other M5+ earthquakes within 300 km of the September 2, 2017 earthquake over the preceding century. The largest was the October 28, 1983, M6.9 Borah Peak earthquake, which struck about 250 km to the northwest of the September 2, 2017 earthquake. The Borah Peak earthquake is the largest known to have occurred in Idaho, and resulted in two fatalities, two injuries, and considerable damage in Challis, Idaho.

Improved Monitoring

The University of Utah Seismograph Stations and the USGS are collaborating to improve earthquake monitoring in the region of the recent seismicity. Eight seismic stations have been installed within 60 miles of the mainshock. Data from these seismic stations are being used to more accurately locate the earthquakes and detect smaller events. These data are helping researchers map the causative faults and will improve our understanding of earthquake hazard in the region.

Earthquake Forecast

The M5.3 Soda Springs Sequence is particularly active, producing more aftershocks on average than other earthquakes of this magnitude. In terms of future larger earthquakes in this area:

- When there are more earthquakes, the chance of a large earthquake is greater, which means that the chance of damage is greater.

- Idaho and Montana experience earthquakes. While earthquakes are not that common, it is also not surprising to see earthquakes in these areas.

- This sequence may have damaging earthquakes in the future, so remember to: Drop, Cover, and Hold on if you feel the ground shaking.

Due to the active and ongoing nature of this sequence, we have developed an earthquake forecast for continuing seismicity. No one can predict the exact time or place of any earthquake, including aftershocks. What our earthquake forecasts do is give us an understanding of the chances of having more earthquakes within a given time period. We calculate this earthquake forecast using a statistical analysis based on past earthquakes in similar tectonic environments, as well as the aftershocks recorded to date for this sequence.

Our forecast changes as time passes due to the decay in the frequency of aftershocks, larger aftershocks that reinvigorate the sequence, and changes in forecast modeling based on the earthquake data collected. Similar to weather models, our models will also change with more data and information. The longer this sequence goes on, the more we learn about what it will do in the future.

We have taken a detailed forecast and developed three scenarios that we consider to be the most likely. These scenarios are for the following month, but earthquakes will continue to be possible at later times. The forecast was last updated on Sept. 28, 2017. We will continue to update the forecast as more information becomes available.

Here are the three scenarios or possibilities for the month starting Sept. 28, 2017, based on earthquake forecast models:

- Scenario #1 (most likely: 90-95% chance):

The sequence will continue to decay over the next month, which means there will be fewer earthquakes. Earthquakes above M3 may be felt by those in the area, and occasional spikes in activity may be accompanied by additional M4 or larger earthquakes, but with none larger than the M5.3 mainshock. While all earthquake sequences decay over time, there are several other possible outcomes, which are listed next. - Scenario #2 (less likely than Scenario #1 but possible with 5-10% chance):

A similar sized or larger earthquake than the M5.3 mainshock may occur. This situation is often referred to as a “doublet” when a similar sized earthquake follows the original earthquake that kicked off the sequence. Doublets have occurred in places around the world, but they are not very common. - Scenario #3 (the least likely scenario but still possible with less than 1% chance):

A much larger earthquake than M5.3 could occur, up to and including the M7 range, in which case we would call what has happened prior to any larger earthquake a foreshock sequence. We have seen this happen in other places around the world, with the most notable being L’Aquila, Italy in 2009. It is important to understand that this is a highly unlikely scenario, but we cannot ignore the possibility of this occurring.

This forecast is for one month, but the sequence may continue past that timeframe. The probabilities will be updated periodically.

What You Can Do About the Earthquakes

If you feel an earthquake, remember to: Drop, Cover, and Hold On. An earthquake may feel small at the beginning but can build in shaking intensity very quickly, so it is best to take the precaution in small earthquakes, as well as larger ones. Preparing for earthquakes is also important - see our Earthquake Preparedness resources. Earthquakes don’t give us any warning that they are coming, so it is important to be prepared for them just in case.

What Scientists are Doing to Learn More About These Earthquakes

Due to its remote location, there is a lot to be learned yet about this sequence. We are working with scientists and students at Utah State University, University of Idaho, and other institutions to get a better understanding of the geologic processes causing these earthquakes. We are assisting with a program of research to determine areas that are most affected, any changes in local hot springs, and other issues.

What Fault is Causing All This Shaking?

We aren’t certain which fault these earthquakes are occurring on, but we have some strong suspects. The specific fault responsible for this earthquake and the subsequent aftershocks is currently under study by the USGS and scientists at Utah State University. Science investigation teams are getting out in the field to deploy temporary seismic instruments and find out more information about the causes and consequences of this earthquake swarm.

The geology of this area is intriguing and complex. The M5.3 earthquake and subsequent aftershocks occurred beneath the Aspen Range of southeastern Idaho, approximately 15 km (9.3 mi) SE of Soda Springs, Idaho, and 33 km (20 mi) north of Montpelier, Idaho. The basic geology of the region consists of folded and thrust-faulted rocks of Permian to Cretaceous age. These thrust faults shifted these rocks from west to east approximately 100 million years ago and created the mountains from southeastern Idaho to western Wyoming, a region termed the Idaho-Wyoming-Utah fold and thrust belt. Subsequent to this compression, the area has been subjected to east-west extension that has created active normal faults.

To the southwest, these faults are clearly seen (the Wasatch Fault, East/West Cache Faults and the East/West Bear Lake Faults). The West and East Bear Lake faults probably continue north of the lake. These two faults are responsible for the formation of these valleys, including the valley through which the Bear River flows from Montpelier to Soda Springs. These normal faults probably started moving several million years ago, and indicators of offset can be seen from Georgetown to east of Bear Lake. The current earthquake sequence could have occurred on one of these faults.

However, there are number of suspects in determining which fault is the main culprit. And indeed, there could be multiple faults at play - in fact, focal mechanisms suggest that several different faults are involved, because there are both normal and strike slip mechanisms. We hope to resolve this issue the coming weeks and months with additional scientific studies.

Teamwork Built this Forecast and the Science Investigation

We’d like to acknowledge our many hard-working partners in Utah State University, University of Utah, Idaho Geological Survey, Yellowstone Volcano Observatory, and other institutions. We’d also like to acknowledge our colleagues in New Zealand, who worked hard in developing forecasts and scenarios in their country. Their hard work has inspired the development of these forecast scenarios.